Philosophy

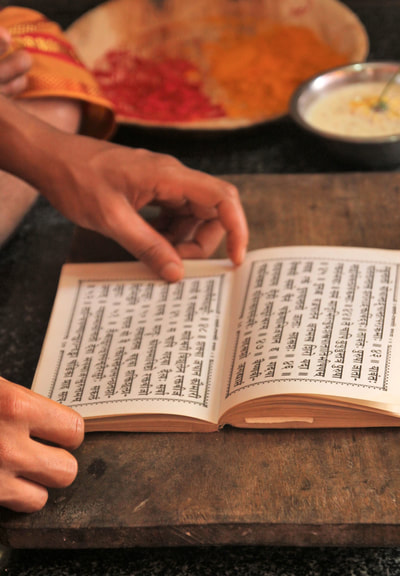

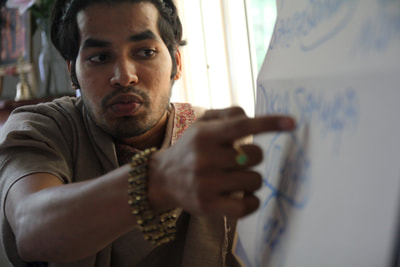

The philosophy classes are going on in the Yogagurukula on daily basis. The texts that are usually lectured and studied include "Yoga Sutra" and "The Bhagavad Gita". Sometimes also texts such as "Yoga Vasista", "Uddhava Gita", "Vivekachudamani" and "Hatha Yoga Pradipika" find their way in our teacher's book holder, "vyasa pita" and the classes truly uplifts everyone. present. '

No previous knowledge of any of these texts or philosophies are necessary.

A notebook, a yearning for the knowledge and an open mind are more important qualities of a student.

Here below you may find a helpful introduction of the different Indian philosophies.

Like any practices or subjects regarding spirituality, a true understanding of the knowledge of the Self takes time and patience..

No previous knowledge of any of these texts or philosophies are necessary.

A notebook, a yearning for the knowledge and an open mind are more important qualities of a student.

Here below you may find a helpful introduction of the different Indian philosophies.

Like any practices or subjects regarding spirituality, a true understanding of the knowledge of the Self takes time and patience..

Introduction

The ancient Indian system of education revolves around the 14 Vidyasthanas or ‘repositories of knowledge’. These are the systems of knowledge that were imparted as education to everyone from ancient times till the early 20th century. They include:

The 4 Vedas

There are six orthodox schools or “darshanas” in Indian philosophy, which all consider the Vedas as the authority for their teachings: Sankhya, Yoga, Vedanta, Mimamsa, Vaisheshika and Nyaya. Nyaya and Vaisheshika together form the Tarka Shastra.

Sankhya Philosophy

Each human being is affected by three types of miseries: The Adhidaivika-, the Adhyatmika- and the Adibhautika misery. Adhibhautika misery is the misery that arises from the five great elements like Earth, Water, Fire, Ether and Air. Examples are earthquakes, cyclones, floods etc.

Adhidaivika miseries are those that arise due to the imbalances created by man, that incur the wrath of the Gods, the different planets and so on, which result in various types of inconveniences and difficulties for humans.

The Adhyatmika miseries are those that are related to both the body and soul of the human beings. These include various types of physical and mental diseases and also those that prevent the spiritual progress of the human beings. These three types of miseries invariably afflict every human being.

Therefore there has been a thorough enquiry into the preventive and curative causes for these miseries. The Sankhya system initially conducted a detailed enquiry to find ways and means to overcome these miseries. First, the curative measures were found to be of two types viz. Drshta and Adrshta.

The Drshta measures were those where both the measures and the effects could easily be cognized. However, the Drshta measures that were practiced were found to be inadequate in washing away the miseries completely and permanently. Therefore, the Adrshta path had to be resorted to, to rid the souls of their miseries, in a complete and permanent manner.

According to the Sankhya philosophy the principle cause for the individual soul to undergo misery is the fact that he thinks he is the performer of all activities. It is actually the Prakrti (Generally translated as ‘Nature’), which is responsible for all the happenings in the life of a human being. The Prakrti is of the form of the three qualities Sattva, Rajas and Tamas and is also the root cause of the entire universe. A human being thinks that he himself is responsible for all the happenings in his life, which is not true according to the Sankhya philosophy. This is due to the fact that he does not realize that it is actually the Prakrti that is responsible for all the happenings.

An example is given to illustrate this aspect. When a person looks into a dirty mirror and sees his face, he is given to think that the dirt actually exists in his own face, rather than on the mirror. Similarly, the ‘Kartrtva’ – ‘doer-ness’ rests with the Prakrti and not the Purusha (the individual soul). But due to the process called ‘’citcchayapatti’’ (shadow of the Prakriti falling on the individual soul, that creates an illusion in the soul) – the individual/Purusha is made to believe that it is he who is the doer.

Therefore, to overcome this wrong notion and to keep himself detached from all the incidents, he has to realize that the individual soul is totally different from the Prakrti and it is the Prakrti and not himself that is responsible for the happenings in human life. Therefore it is stated that the ‘Prakrti-Purusha-viveka‘; the realization of the distinction between Prakrti and the individual soul by realizing the exact nature of both these entities, is the sole and best means to get rid of all the miseries and attain fulfillment.

The Sankhya system of philosophy is known as ‘Jnana-marga’ or Avyaktamarga. The references to the Sankhya system are available in the Srimadbhagavatam, Bhagavadgita and other important works. However, the principle work that is accepted as the primary authority on the Sankhya system is the work called Sankhyakarika of Iswarakrishna who is said to belong to third century AD. Further, the Sankhya system is referred to extensively in the Brahmasutras of Maharshi Vyasa as the primary rival system of the Vedanta philosophy. This is due to the fact that the Vedanta system advocates the path of Bhakti, as opposed to the path of Jnana. The Sankhya system of Jnana advocates worshipping a formless, attributeless entity. It also does not accept the existence of a separate entity called ‘Iswara’ – God. In fact, it neither refutes nor goes on to prove the existence of Iswara. It is totally silent on this aspect. And hence, it is called as ‘’Niriswara Sankhya’’ or the Sankhya system that does not accept the existence of Iswara. The word Sankhya comes from the word Sankhyaa, which means all of the following:

The Sankhya system believes that Prakrti is the root cause of the world of objects. Since this is the first principle of this Universe, it is also called Pradhana and Mulaprakrti. Prakrti consists of the three gunas called Sattva, Rajas and Tamas. Purusha (the individual soul) is of the nature of pure consciousness. It is devoid of all attributes and is unaffected by all happenings just like the leaf of a lotus is not tainted by water even though it exists within water. These are the principle theories of the Sankhya system.

To conclude it can be said that there are two practical ways advocated by the Indian systems of philosophy namely Sankhya and Yoga. Sankhya is the path of Jnana – knowledge and the Yoga is the path of Bhakti – devotion.

Yoga philosophy

The principle text on Yoga philosophy is the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali dated to the 2nd century BCE. The text firmly rests on the tradition of Sankhya philosophy, essentially accepting all the concepts of this theory. The introduction of two premises constitutes the main difference between these two schools of thought; the existence of a deity, Ishvara, and the practical approach to attain liberation, the ashtanga yoga system.

Of the six astikas or orthodox schools of thought in Indian philosophy, Yoga is the only one to be characterized as a practical philosophy; an “abhyasa shastra”, taught to be practiced, while the other five are characterized as “jijnasa shastras”, focusing on the discussion and clarification of the theory. This practical approach of the Yoga philosophy is stated already in the first of the Yoga Sutras; “Atha yoganushasanam”; Now starts the instruction in yoga.

The Yoga Sutras present the philosophy methodically in four chapters. The first, “Samadhi pada”, defines yoga and explains the process of attaining it. The second chapter, “Sadhana pada”, portrays the ashtanga system; the practical means to achieve yoga. The two last chapters, “Vibuthi pada” and “Kaivalya pada” describe the fruits of yoga.

Yoga is defined as samadhi, the state in which there is complete restraint of the mind-vrittis (“Yogaschittavrittinirodhaha”). The main means to achieve this is “abhyasa”, practice, and “vairagya”, dispassion, as presented in the first chapter. The very practical means to develop these two qualities are presented in the second chapter; Kriya yoga for beginners and Ashtanga yoga for the somewhat more advanced practitioners.

The eight limbs of ashtanga yoga are yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana and samadhi. The first five limbs are considered external aids while the last three are considered internal aids.

The first two limbs, yama and niyama, are rules for right living and the foundation for the practice of the other limbs. The five yamas represent the rules for conduct towards the external world, whereas the five niyamas are focused on conduct beneficial to a person’s inner world. The yamas are ahimsa, satya, asteya, bramhacharya and aparigraha, and can be translated as non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, appropriate use of vital essence (often translated as sexual abstinence) and non-greed. These rules are to be followed by everyone, but for a yogi, they represent “the great vow” and are not to be crossed at any time or for any reason. This will give steadiness in the practice of yama, giving the promised fruits, like abandonment of hostility in the presence of the one practicing ahimsa or great vitality for the one practicing bramhacharya.

The niyamas, often translated as “observances”, are positive actions; instructions to be followed. They are listed as schoucha, santosha, tapas, svadhyaya and Ishvarapranidhana and can be translated as cleanliness, contentment, austerity, self-study and devotion to God. External or bodily cleanliness, but even more so, internal or mental cleanliness, along with contentment, austerity, self-study and devotion to God are practices that will increase the happiness of mind (“sattvic” mind), the knowledge of oneself and also increase dispassion.

Asana is the posture in which one practices the internal limbs of yoga with steadiness and a pleasant mind. There are two means to achieve skill in asana; to release the effort and to focus the mind on infinity. The fruit promised from skill in asana is the cessation of duality.

Pranayama is the method of changing the breathing pattern and is to be practiced only when one has achieved steadiness in asana. The main benefit is the ability to control the mind. This is essential to the next limb, pratyahara, explained as withdrawing the sense organs from their external objects, causing the senses to merge in the mind.

Dharana, dhyana and samadhi are the internal means to achieve yoga or samadhi, making samadhi both a method and an aim. Dharana is described as the concentration of the mind on an object. Dhyana is the continuous flow of concentration on the chosen object.

In samadhi the mind merges with the object. Samadhi is of two kinds, sabija and nirbija samadhi. Sabija samadhi is further divided into savitarka, savichara, sananda and sasmita samadhi. In these stages of sabija samadhi, there is a gradual differentiation between the known (the object), the knower and the process of knowing, until they merge in nirbija samadhi, and the mind takes the form of the object without interpretations, conceptions or awareness of the process. All fluctuations of the mind are restrained and the Seer rests in his own nature (“Tada drashtuhsvarupevastanam”). The nirbija stage of samadhi is liberation.

Although in the Yoga philosophy the ashtanga system is presented as the main method, liberation can also be achieved by Ishvarapranidhana; devotion to Ishvara. Ishvara is described as the supreme soul, omniscient, untouched by afflictions, karma and the effects of karma. Ishvara’s name and form can only be expressed by the sound OM, and the sound should therefore be repeated and contemplated upon. This will give knowledge of the real nature of purusha and prakrti, facilitating the practice of samadhi. Ishvarapranidhana as means to achieve liberation is the cause for characterising Yoga as the path of Bhakti – devotion.

Vedanta Shastra

What is ‘life’? What is its main aim? Who am ‘I’? What is the entity that is to be understood by the concept that is denoted by the word ‘I’? These are some questions that have been perturbing the minds of intellectuals and thinkers from time immemorial.

Ancient Indian philosophers conducted specialized studies to find infallible and precise answers to these questions by means of both internal and external enquiry. This enquiry was based not on their own intellect, but on the words of the ancient seers who had intuitional knowledge that was revealed to them by the grace of none other than the Supreme Lord Himself. These words, which constitute a wide and deep body of divine knowledge, are known as the ‘Vedas’.

The Vedas represent such a vast body of literature that it is very difficult to understand its purport in a simple manner. Therefore the Upanishads emerged, to convey the purport of the Vedas relatively easy and comprehensible. The word “Vedanta” literally means "end (or culmination) of the Vedas". The three most important sources for Vedanta are Upanishads (commentaries on the Vedas), the Bramha Sutras and Bhagavad Gita. The original philosophical text of the Vedanta, the Brahma Sutras of Badarayana, is purportedly a condensation and systematisation of Upanishadic wisdom, so concise and abbreviated that it is considered completely incomprehensible. This ambiguity allowed a huge number of schools and sub schools to develop, each one based on commentaries on the Upanishads, Brahma sutras, Gita, and other authoritative texts. Different interpretations of the fundamental texts of Vedanta have given rise to three main schools: Advaita (monistic or nondual) of Adi Shankaracharya, Visishtadvaita (qualified non- dualism) of Ramanuja and Dvaita (dualism) of Madhva. There are in addition a variety of other less influential schools like the Vallabha School, Nimbarka school, Bhaskara school and so on, but these are the three most important.

Vedanta generally deals with four topics:

A Summary of the main Vedantic Schools

Advaita Vedanta

According to the Advaita school, Brahman alone is Real, the one without a second, and that same Ultimate Reality is identical with one's true self (atman), and transcends all forms (nirguna - without qualities). Although this world has emanated from Brahman and will return to Him at the end of creation, it possesses only relative reality. The entire universe is simply an appearance, although one that is objectively real to one who has not attained to Brahman.

Brahman, which is an infinite being, consciousness and bliss (sacchidananda), is the sole reality. God (Ishvara), the World (Prakriti or Maya), and the individual souls (Jivatma) are all ultimately of the same nature, which is Brahman. The difference between them is only apparent, brought about by Ajnana or metaphysical ignorance also known as ‘nescience’. Liberation (Moksha) involves realizing that one's real nature, the Atman, is identical with Brahman. Liberation is therefore an act of knowledge rather than an act of devotion. In this respect Advaita differs from the two other main Vedantic schools.

Visistadvaita Vedanta

Visishtadvaita teaches that Brahman, who is also called Isvara ("Lord"), is not impersonal but a personality endowed with all the superior qualities like knowledge, power and love and is totally devoid of all inferior qualities and impurities. There is a multiplicity of Jivas (Souls), which are identical with one another, though separate from one another and from the Supreme Brahman. This world, which is of the nature of insentient Prakriti, is different from both Brahman and from the Jivas. However individual souls (Jivas) and the universe (praki) exist eternally as the body of God, who is Spirit or Soul in relation to them. They are therefore fully under His control. God, souls and matter together form an inseparable unity, but there is still that distinction between them. Liberation (Moksha) is obtained through devotion to Isvara. It is only by His grace that Moksha can be secured.

Dvaita Vedanta

The Dvaita system is similar to Visishtadvaita. However, it carries the differences still further and affirms duality instead of unity. Brahman is Hari or Vishnu. He has a transcendental form, and manifests on Earth in the form of Avatars (Incarnations). There are an infinite number of souls (cit), which are each point-like. Matter (acit) is real but non-conscious. Reality is defined as a five-fold distinction - between God and souls, God and matter, souls and souls, souls and matter, and material objects.

The cause of bondage is the Will of the Supreme and the ignorance of the soul. Liberation is primarily through Bhakti (devotion to God). Liberated souls never lose their individuality; they are only released from the bondage of ‘Samsara’. Thus each of the tree schools treads a relatively different path. It is the opinion of many that the same reality is seen from different angles, hence the difference in their cognizance. The same object can seem to look differently when seen from different points of view, as is a common experience. It can also be taken that the three schools are to be seen as seeker-dependant.

For a seeker who is more intellectual, the philosophy of Advaita appeals more, while for the emotionally inclined the path of devotion (Bhakti) to reach the Supreme, as described by Acharya Ramanuja, is definitely better. The philosophy of Madhvacharya is more inclined towards the philosophy of Nyaya. To understand the complete Diaspora of the philosophy of Vedanta it requires a deep and long study. However it can be safely concluded that all the three Acharyas are to be worshipped and trusted and following any one path with conviction will lead the seeker to attain the ultimate aim of human life – liberation.

Meemamsa Darshana

The Meemamsa Darshana is one of the 14 Vidyasthanas as well as one of the orthodox systems of Indian philosophy. The word ‘Meemamsa’ means ‘enquiry’.

Introduction to the Meemamsa system of Philosophy

The entire gamut of literature of the Vedas is the principle source of all knowledge, spiritual as well as material. Sri Sankaracharya defines the Vedas as a huge body of knowledge by saying ‘Vedo hi Jnanaraashih’. The Meemamsa system is said to be the ‘Upa-Anga’ (subsidiary limb) of the Vedas. The principle exertion of the Vedas is to lay down the ‘do’s and ‘don’t’s with regard to the spiritual-, physical-, social-, personal- and all other spheres of human life.

Kumarila Bhatta, one of the premier exponents of the Meemamsa philosophy, says “That literature which lay down the ‘do’s and ‘don’t’s by any means that is eternal or non-eternal, natural or artificial, is known as a ‘Shastra’”. Further it has been mentioned by Maharishi Vyasa that the Vedas are the Supreme ‘Shastra’ and there is no Shastra that supersedes the Vedas (“Vedat shastram param nasti”). The Vedas are so vast in nature and extent that it is extremely difficult for any single ordinary person to entirely learn it by heart and understand it.

Further it is couched in an exclusively difficult Sanskrit language that differs from the regular Sanskrit language found in other literature like Ramayana and Mahabharata. Therefore there was a dire need for a separate system of thought to interpret this huge body of literature and make it understandable. It is to fill up this void that the Meemamsa system came in to being. In addition to this, when one studies the Vedic texts, there seem to be some fallacies in them like repetitions, contradictions and other types of errors. These types of fallacies are apparently visible when a huge body of literature is studied without a concrete system of knowledge to set the rules of interpretation. The purpose of the Meemamsa system is also to set these rules of interpretation of the different sentences and passages, understand the technical terms, and to overcome the doubts or wrong notions regarding the apparent existence of repetitions, contradictions, and other types of errors in the Vedic literature.

The Literature of Meemamsa :

The Meemamsa system of philosophy has its origins in the Meemamsa Sutras authored by Sage Jaimini. These Sutras (aphorisms) number more than a thousand and are divided into twelve chapters popularly known as ‘Dwadasha-Lakshani’ (a compendium having twelve chapters). Each chapter or Adhyaya is further divided into four Padas or quarters. These Sutras of Sage Jaimini were commented upon by another Sage called Sabaraswami in the Saabara-Bhashya. A great scholar called Kumarila Bhatta (a predecessor of Adi Shankaracharya), belonging to the 8th century AD, authored the Shloka-Vartika and Tantra Vartika, another type of commentary on these Sutras, and thus made it a complete system of Philosophy.

Schools of Meemamsa :

As time progressed, two different schools developed in the Meemamsa system of philosophy. While the more orthodox and conservative older school owes its allegiance to a great scholar called Prabhakara and is known as the ‘Praabhaakara’ school, the later and not-so-orthodox school started by Kumarila Bhatta is known as the ‘Bhaatta school’. Both the schools have influenced the different schools of the Vedanta system of philosophy deeply.

Method of interpretation used in Meemamsa system of philosophy:

A particular Vedic passage which meaning or application is apparently ambiguous is taken up for discussion. Based on this, an ‘Adhikarana’ or locus of discussion is started. An Adhikarana contains six aspects viz. Vishaya (topic of discussion) Visaya (doubt) Purva-paksha (the apparent / incorrect view) Uttara Paksha (the correct, final view) Akshepa (objections on the view expressed above) Samadhana (reply to the objections raised). When an Adhikarana is started, first of all the Vedic passage or sentence being the topic of discussion is presented. Then the different possible meanings of the apparently ambiguous passage are mentioned. The incorrect view(s) is (are) first mentioned along with the basis (yukti) for substantiating them. Then the incorrect view is refuted by giving the logical reasons for this, and the correct and final view is presented along with the logical reasons. Further objections to this, if any, are raised, and the answers to those objections too are given and then the final concept obtained by the discussion is reiterated and declared. These are the aspects that constitute an ‘Adhikarana’.

In the Meemamsa system of philosophy authored by Sage Jaimini, there are an amazing one thousand Adhikaranas. Each of these Adhikaranas has given rise to concrete logical statutes that are known as ‘Nyayas’ and these too are one thousand in number. There is also a set of standard rules for interpreting the Vedic passages taken up for discussion. These are known as the “Taatparya-nirnaayaka-yuktis” or the logical reasoning that is useful in deciphering, analyzing and interpreting the exact meaning of the Vedic passages. They are as follows:

Vaisheshika – The Prameya Shastra

While the Nyaya Darshana deals extensively with the Pramanas or the means of knowledge, the Vaisheshika deals with the objects of knowledge that is obtained by means of the Pramanas. Vaisheshika attempts to identify and classify the entities that present themselves to human perception. It explains the nature of the world with seven categories: Dravya (substance), guna (quality), karma (action), samanya (universal), vishesha (particular), samavaya (inherence) and abhava (non-existence).

Vaisheshika contends that every effect is a fresh creation or a new beginning. Thus this system refutes the theory of pre-existence of the effect in the cause. Kanada does not discuss much on God. But the later commentators refer to God as the Supreme Soul, perfect and eternal. This system accepts that God (Ishvara) is the efficient cause of the world. The eternal atoms are the material cause of the world. Vaisheshika recognizes nine ultimate substances; five material and four non-material.

The five material substances are earth, water, fire, air and akasha. The four non-material substances are space, time, soul and mind. Earth, water, fire and air are atomic, but akasha is non-atomic and infinite. Space and time are infinite and eternal. The concept of soul is comparable to that of the self or atman. This system considers consciousness as an accidental property. In other words, when the soul associates itself to the body, only then it ‘acquires’ consciousness.

Thus, consciousness is not considered an essential quality of the soul. The mind (manas) is accepted as an atomic but indivisible and eternal substance. The mind helps to establish the contact of the self to the external world objects. The soul develops attachment to the body owing to ignorance, identifying itself with the body and mind. The soul is trapped in the bondage of karma as a consequence of actions resulted from countless desires and passions. It can be free from the bondage only if it becomes free from actions. Liberation follows the cessation of the actions.

This is but a brief introduction to the Tarka Shastra. This shastra (school of thought) is said to be invariably required for the study and proper understanding of any other system of thought and hence is rightly known as ‘Sarva-shastra-upakarakam’.

Tarka Shastra

The Tarka Shastra is one of the most important knowledge systems as it is mentioned in the Manu Smriti that all the Vedic texts as well as the teachings of the ancient seers are to be interpreted only in the light of correct and precise logic (Tarka) and thus properly understood. The Tarka Shastra consists of two principal streams of knowledge, viz. the Nyaya and the Vaisheshika. The Nyaya Darshana, which is also one of the six orthodox systems (darsana) of Indian philosophy, is important for its analysis of logic and epistemology.

The major contribution of the Nyaya system is its working out in profound detail the reasoning method of inference. Like the other systems, its ultimate concern is to bring an end to man's suffering, which results from ignorance of reality. Liberation is attained through right knowledge. Nyaya is thus concerned with the means of right knowledge. As mentioned earlier, in its metaphysics, Nyaya is allied to the Vaisheshika system, and the two schools were often combined from about the 14th century to form a unified ‘Tarka-Shastra’.

Its principal text is the Nyaya-sutras, ascribed to Gautama (c. 2nd century BC). On the other hand, the Vaisheshika, which was founded in the 2nd–3rd century AD by sage Kanada, is the complimentary school of thought which, when combined with Nyaya, forms the Nyaya-Vaisheshika school.

Nyaya Shastra – The Pramana Shastra

The four methods (Pramanas) of establishing true identity of a phenomenon or an object according to the Nyaya School are: Perception (Pratyaksha), Inference {Anumana), Comparison {Upamana} and Verbal Testimony (Aptavakya). Perception is the recognition and knowledge of the objects produced by their contact with various sense organs such as of sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell and the mind. Though it includes observation, it certainly embraces much more than that. Inference is the knowledge of the objects through the apprehension of some sign, which is invariably related to the inferred object. This is best illustrated by the following oft-quoted (though now outmoded) example "The hill is burning because it smokes and whatever smokes is burning." The order of events that take place when we infer this is: first the apprehension of the smoke in the hill, second the recollection of the universal relation between smoke and fire, and third the recognition of the fire in the hill.

An inference must also fulfill certain other essential requirements to be valid. Firstly, there should be a relation of agreement in presence (anvaya) between two things, i.e., in all cases where one is present, the other should also be present, e.g. wherever there is smoke there is fire. Secondly, there should also be uniform agreement in absence between them (vyatireka) e.g. wherever there is no smoke, there is no fire. Thirdly, no contradictory instance should be observed where one of them is present without the other (vyabhicaragraha).

Comparison is the knowledge of the object or phenomenon obtained by the establishment of a relation between a name and object so named or between a word and its denotation. This is illustrated by the following example: A man is told that an animal with a certain description is a cow. When he sees an animal for the first time, which particularly fits the description, he concludes by comparison that what he is seeing is a cow. The fourth method of establishing the identity of an object is by testimony (aptavakya), i.e. knowledge of the perceived and unperceived objects derived from the statement of authoritative sources, viz. scriptures such as the Vedas or the sayings of saints and sages.

This source of knowledge has been much criticized by Western scholars with the claim that utter acceptance of the authority of the Vedas has been a limiting factor and hindrance in the development of proper reasoning. It is important to note that for Indians their theories and philosophies were not of academic interest only. They actually lived those ideologies and also applied them in their practical sciences.

Recommended literature :

YOGA SUTRA of Patanjali, THE BHAGAVAD GITA, HATHA YOGA PRADIPIKA by Swami Swatmarama

The ancient Indian system of education revolves around the 14 Vidyasthanas or ‘repositories of knowledge’. These are the systems of knowledge that were imparted as education to everyone from ancient times till the early 20th century. They include:

The 4 Vedas

- Rig Veda

- Yajur Veda

- Sama Veda

- Atharva veda

- Shiksha

- Vyakarana

- Chandas

- Niruktha

- Jyothisha, and Kalpa

- The Mimamasa Shastra

- The Nyaya or the Tarka Shastra

- Purana

- Dharma Shastra

There are six orthodox schools or “darshanas” in Indian philosophy, which all consider the Vedas as the authority for their teachings: Sankhya, Yoga, Vedanta, Mimamsa, Vaisheshika and Nyaya. Nyaya and Vaisheshika together form the Tarka Shastra.

Sankhya Philosophy

Each human being is affected by three types of miseries: The Adhidaivika-, the Adhyatmika- and the Adibhautika misery. Adhibhautika misery is the misery that arises from the five great elements like Earth, Water, Fire, Ether and Air. Examples are earthquakes, cyclones, floods etc.

Adhidaivika miseries are those that arise due to the imbalances created by man, that incur the wrath of the Gods, the different planets and so on, which result in various types of inconveniences and difficulties for humans.

The Adhyatmika miseries are those that are related to both the body and soul of the human beings. These include various types of physical and mental diseases and also those that prevent the spiritual progress of the human beings. These three types of miseries invariably afflict every human being.

Therefore there has been a thorough enquiry into the preventive and curative causes for these miseries. The Sankhya system initially conducted a detailed enquiry to find ways and means to overcome these miseries. First, the curative measures were found to be of two types viz. Drshta and Adrshta.

The Drshta measures were those where both the measures and the effects could easily be cognized. However, the Drshta measures that were practiced were found to be inadequate in washing away the miseries completely and permanently. Therefore, the Adrshta path had to be resorted to, to rid the souls of their miseries, in a complete and permanent manner.

According to the Sankhya philosophy the principle cause for the individual soul to undergo misery is the fact that he thinks he is the performer of all activities. It is actually the Prakrti (Generally translated as ‘Nature’), which is responsible for all the happenings in the life of a human being. The Prakrti is of the form of the three qualities Sattva, Rajas and Tamas and is also the root cause of the entire universe. A human being thinks that he himself is responsible for all the happenings in his life, which is not true according to the Sankhya philosophy. This is due to the fact that he does not realize that it is actually the Prakrti that is responsible for all the happenings.

An example is given to illustrate this aspect. When a person looks into a dirty mirror and sees his face, he is given to think that the dirt actually exists in his own face, rather than on the mirror. Similarly, the ‘Kartrtva’ – ‘doer-ness’ rests with the Prakrti and not the Purusha (the individual soul). But due to the process called ‘’citcchayapatti’’ (shadow of the Prakriti falling on the individual soul, that creates an illusion in the soul) – the individual/Purusha is made to believe that it is he who is the doer.

Therefore, to overcome this wrong notion and to keep himself detached from all the incidents, he has to realize that the individual soul is totally different from the Prakrti and it is the Prakrti and not himself that is responsible for the happenings in human life. Therefore it is stated that the ‘Prakrti-Purusha-viveka‘; the realization of the distinction between Prakrti and the individual soul by realizing the exact nature of both these entities, is the sole and best means to get rid of all the miseries and attain fulfillment.

The Sankhya system of philosophy is known as ‘Jnana-marga’ or Avyaktamarga. The references to the Sankhya system are available in the Srimadbhagavatam, Bhagavadgita and other important works. However, the principle work that is accepted as the primary authority on the Sankhya system is the work called Sankhyakarika of Iswarakrishna who is said to belong to third century AD. Further, the Sankhya system is referred to extensively in the Brahmasutras of Maharshi Vyasa as the primary rival system of the Vedanta philosophy. This is due to the fact that the Vedanta system advocates the path of Bhakti, as opposed to the path of Jnana. The Sankhya system of Jnana advocates worshipping a formless, attributeless entity. It also does not accept the existence of a separate entity called ‘Iswara’ – God. In fact, it neither refutes nor goes on to prove the existence of Iswara. It is totally silent on this aspect. And hence, it is called as ‘’Niriswara Sankhya’’ or the Sankhya system that does not accept the existence of Iswara. The word Sankhya comes from the word Sankhyaa, which means all of the following:

- Right knowledge

- Discussions/enquiry

- Number

The Sankhya system believes that Prakrti is the root cause of the world of objects. Since this is the first principle of this Universe, it is also called Pradhana and Mulaprakrti. Prakrti consists of the three gunas called Sattva, Rajas and Tamas. Purusha (the individual soul) is of the nature of pure consciousness. It is devoid of all attributes and is unaffected by all happenings just like the leaf of a lotus is not tainted by water even though it exists within water. These are the principle theories of the Sankhya system.

To conclude it can be said that there are two practical ways advocated by the Indian systems of philosophy namely Sankhya and Yoga. Sankhya is the path of Jnana – knowledge and the Yoga is the path of Bhakti – devotion.

Yoga philosophy

The principle text on Yoga philosophy is the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali dated to the 2nd century BCE. The text firmly rests on the tradition of Sankhya philosophy, essentially accepting all the concepts of this theory. The introduction of two premises constitutes the main difference between these two schools of thought; the existence of a deity, Ishvara, and the practical approach to attain liberation, the ashtanga yoga system.

Of the six astikas or orthodox schools of thought in Indian philosophy, Yoga is the only one to be characterized as a practical philosophy; an “abhyasa shastra”, taught to be practiced, while the other five are characterized as “jijnasa shastras”, focusing on the discussion and clarification of the theory. This practical approach of the Yoga philosophy is stated already in the first of the Yoga Sutras; “Atha yoganushasanam”; Now starts the instruction in yoga.

The Yoga Sutras present the philosophy methodically in four chapters. The first, “Samadhi pada”, defines yoga and explains the process of attaining it. The second chapter, “Sadhana pada”, portrays the ashtanga system; the practical means to achieve yoga. The two last chapters, “Vibuthi pada” and “Kaivalya pada” describe the fruits of yoga.

Yoga is defined as samadhi, the state in which there is complete restraint of the mind-vrittis (“Yogaschittavrittinirodhaha”). The main means to achieve this is “abhyasa”, practice, and “vairagya”, dispassion, as presented in the first chapter. The very practical means to develop these two qualities are presented in the second chapter; Kriya yoga for beginners and Ashtanga yoga for the somewhat more advanced practitioners.

The eight limbs of ashtanga yoga are yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana and samadhi. The first five limbs are considered external aids while the last three are considered internal aids.

The first two limbs, yama and niyama, are rules for right living and the foundation for the practice of the other limbs. The five yamas represent the rules for conduct towards the external world, whereas the five niyamas are focused on conduct beneficial to a person’s inner world. The yamas are ahimsa, satya, asteya, bramhacharya and aparigraha, and can be translated as non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, appropriate use of vital essence (often translated as sexual abstinence) and non-greed. These rules are to be followed by everyone, but for a yogi, they represent “the great vow” and are not to be crossed at any time or for any reason. This will give steadiness in the practice of yama, giving the promised fruits, like abandonment of hostility in the presence of the one practicing ahimsa or great vitality for the one practicing bramhacharya.

The niyamas, often translated as “observances”, are positive actions; instructions to be followed. They are listed as schoucha, santosha, tapas, svadhyaya and Ishvarapranidhana and can be translated as cleanliness, contentment, austerity, self-study and devotion to God. External or bodily cleanliness, but even more so, internal or mental cleanliness, along with contentment, austerity, self-study and devotion to God are practices that will increase the happiness of mind (“sattvic” mind), the knowledge of oneself and also increase dispassion.

Asana is the posture in which one practices the internal limbs of yoga with steadiness and a pleasant mind. There are two means to achieve skill in asana; to release the effort and to focus the mind on infinity. The fruit promised from skill in asana is the cessation of duality.

Pranayama is the method of changing the breathing pattern and is to be practiced only when one has achieved steadiness in asana. The main benefit is the ability to control the mind. This is essential to the next limb, pratyahara, explained as withdrawing the sense organs from their external objects, causing the senses to merge in the mind.

Dharana, dhyana and samadhi are the internal means to achieve yoga or samadhi, making samadhi both a method and an aim. Dharana is described as the concentration of the mind on an object. Dhyana is the continuous flow of concentration on the chosen object.

In samadhi the mind merges with the object. Samadhi is of two kinds, sabija and nirbija samadhi. Sabija samadhi is further divided into savitarka, savichara, sananda and sasmita samadhi. In these stages of sabija samadhi, there is a gradual differentiation between the known (the object), the knower and the process of knowing, until they merge in nirbija samadhi, and the mind takes the form of the object without interpretations, conceptions or awareness of the process. All fluctuations of the mind are restrained and the Seer rests in his own nature (“Tada drashtuhsvarupevastanam”). The nirbija stage of samadhi is liberation.

Although in the Yoga philosophy the ashtanga system is presented as the main method, liberation can also be achieved by Ishvarapranidhana; devotion to Ishvara. Ishvara is described as the supreme soul, omniscient, untouched by afflictions, karma and the effects of karma. Ishvara’s name and form can only be expressed by the sound OM, and the sound should therefore be repeated and contemplated upon. This will give knowledge of the real nature of purusha and prakrti, facilitating the practice of samadhi. Ishvarapranidhana as means to achieve liberation is the cause for characterising Yoga as the path of Bhakti – devotion.

Vedanta Shastra

What is ‘life’? What is its main aim? Who am ‘I’? What is the entity that is to be understood by the concept that is denoted by the word ‘I’? These are some questions that have been perturbing the minds of intellectuals and thinkers from time immemorial.

Ancient Indian philosophers conducted specialized studies to find infallible and precise answers to these questions by means of both internal and external enquiry. This enquiry was based not on their own intellect, but on the words of the ancient seers who had intuitional knowledge that was revealed to them by the grace of none other than the Supreme Lord Himself. These words, which constitute a wide and deep body of divine knowledge, are known as the ‘Vedas’.

The Vedas represent such a vast body of literature that it is very difficult to understand its purport in a simple manner. Therefore the Upanishads emerged, to convey the purport of the Vedas relatively easy and comprehensible. The word “Vedanta” literally means "end (or culmination) of the Vedas". The three most important sources for Vedanta are Upanishads (commentaries on the Vedas), the Bramha Sutras and Bhagavad Gita. The original philosophical text of the Vedanta, the Brahma Sutras of Badarayana, is purportedly a condensation and systematisation of Upanishadic wisdom, so concise and abbreviated that it is considered completely incomprehensible. This ambiguity allowed a huge number of schools and sub schools to develop, each one based on commentaries on the Upanishads, Brahma sutras, Gita, and other authoritative texts. Different interpretations of the fundamental texts of Vedanta have given rise to three main schools: Advaita (monistic or nondual) of Adi Shankaracharya, Visishtadvaita (qualified non- dualism) of Ramanuja and Dvaita (dualism) of Madhva. There are in addition a variety of other less influential schools like the Vallabha School, Nimbarka school, Bhaskara school and so on, but these are the three most important.

Vedanta generally deals with four topics:

- Brahman (the Supreme or Universal soul)

- Jivatman (the individual soul)

- The Creation of the world

- Moksha (liberation), the final goal of human life

A Summary of the main Vedantic Schools

Advaita Vedanta

According to the Advaita school, Brahman alone is Real, the one without a second, and that same Ultimate Reality is identical with one's true self (atman), and transcends all forms (nirguna - without qualities). Although this world has emanated from Brahman and will return to Him at the end of creation, it possesses only relative reality. The entire universe is simply an appearance, although one that is objectively real to one who has not attained to Brahman.

Brahman, which is an infinite being, consciousness and bliss (sacchidananda), is the sole reality. God (Ishvara), the World (Prakriti or Maya), and the individual souls (Jivatma) are all ultimately of the same nature, which is Brahman. The difference between them is only apparent, brought about by Ajnana or metaphysical ignorance also known as ‘nescience’. Liberation (Moksha) involves realizing that one's real nature, the Atman, is identical with Brahman. Liberation is therefore an act of knowledge rather than an act of devotion. In this respect Advaita differs from the two other main Vedantic schools.

Visistadvaita Vedanta

Visishtadvaita teaches that Brahman, who is also called Isvara ("Lord"), is not impersonal but a personality endowed with all the superior qualities like knowledge, power and love and is totally devoid of all inferior qualities and impurities. There is a multiplicity of Jivas (Souls), which are identical with one another, though separate from one another and from the Supreme Brahman. This world, which is of the nature of insentient Prakriti, is different from both Brahman and from the Jivas. However individual souls (Jivas) and the universe (praki) exist eternally as the body of God, who is Spirit or Soul in relation to them. They are therefore fully under His control. God, souls and matter together form an inseparable unity, but there is still that distinction between them. Liberation (Moksha) is obtained through devotion to Isvara. It is only by His grace that Moksha can be secured.

Dvaita Vedanta

The Dvaita system is similar to Visishtadvaita. However, it carries the differences still further and affirms duality instead of unity. Brahman is Hari or Vishnu. He has a transcendental form, and manifests on Earth in the form of Avatars (Incarnations). There are an infinite number of souls (cit), which are each point-like. Matter (acit) is real but non-conscious. Reality is defined as a five-fold distinction - between God and souls, God and matter, souls and souls, souls and matter, and material objects.

The cause of bondage is the Will of the Supreme and the ignorance of the soul. Liberation is primarily through Bhakti (devotion to God). Liberated souls never lose their individuality; they are only released from the bondage of ‘Samsara’. Thus each of the tree schools treads a relatively different path. It is the opinion of many that the same reality is seen from different angles, hence the difference in their cognizance. The same object can seem to look differently when seen from different points of view, as is a common experience. It can also be taken that the three schools are to be seen as seeker-dependant.

For a seeker who is more intellectual, the philosophy of Advaita appeals more, while for the emotionally inclined the path of devotion (Bhakti) to reach the Supreme, as described by Acharya Ramanuja, is definitely better. The philosophy of Madhvacharya is more inclined towards the philosophy of Nyaya. To understand the complete Diaspora of the philosophy of Vedanta it requires a deep and long study. However it can be safely concluded that all the three Acharyas are to be worshipped and trusted and following any one path with conviction will lead the seeker to attain the ultimate aim of human life – liberation.

Meemamsa Darshana

The Meemamsa Darshana is one of the 14 Vidyasthanas as well as one of the orthodox systems of Indian philosophy. The word ‘Meemamsa’ means ‘enquiry’.

Introduction to the Meemamsa system of Philosophy

The entire gamut of literature of the Vedas is the principle source of all knowledge, spiritual as well as material. Sri Sankaracharya defines the Vedas as a huge body of knowledge by saying ‘Vedo hi Jnanaraashih’. The Meemamsa system is said to be the ‘Upa-Anga’ (subsidiary limb) of the Vedas. The principle exertion of the Vedas is to lay down the ‘do’s and ‘don’t’s with regard to the spiritual-, physical-, social-, personal- and all other spheres of human life.

Kumarila Bhatta, one of the premier exponents of the Meemamsa philosophy, says “That literature which lay down the ‘do’s and ‘don’t’s by any means that is eternal or non-eternal, natural or artificial, is known as a ‘Shastra’”. Further it has been mentioned by Maharishi Vyasa that the Vedas are the Supreme ‘Shastra’ and there is no Shastra that supersedes the Vedas (“Vedat shastram param nasti”). The Vedas are so vast in nature and extent that it is extremely difficult for any single ordinary person to entirely learn it by heart and understand it.

Further it is couched in an exclusively difficult Sanskrit language that differs from the regular Sanskrit language found in other literature like Ramayana and Mahabharata. Therefore there was a dire need for a separate system of thought to interpret this huge body of literature and make it understandable. It is to fill up this void that the Meemamsa system came in to being. In addition to this, when one studies the Vedic texts, there seem to be some fallacies in them like repetitions, contradictions and other types of errors. These types of fallacies are apparently visible when a huge body of literature is studied without a concrete system of knowledge to set the rules of interpretation. The purpose of the Meemamsa system is also to set these rules of interpretation of the different sentences and passages, understand the technical terms, and to overcome the doubts or wrong notions regarding the apparent existence of repetitions, contradictions, and other types of errors in the Vedic literature.

The Literature of Meemamsa :

The Meemamsa system of philosophy has its origins in the Meemamsa Sutras authored by Sage Jaimini. These Sutras (aphorisms) number more than a thousand and are divided into twelve chapters popularly known as ‘Dwadasha-Lakshani’ (a compendium having twelve chapters). Each chapter or Adhyaya is further divided into four Padas or quarters. These Sutras of Sage Jaimini were commented upon by another Sage called Sabaraswami in the Saabara-Bhashya. A great scholar called Kumarila Bhatta (a predecessor of Adi Shankaracharya), belonging to the 8th century AD, authored the Shloka-Vartika and Tantra Vartika, another type of commentary on these Sutras, and thus made it a complete system of Philosophy.

Schools of Meemamsa :

As time progressed, two different schools developed in the Meemamsa system of philosophy. While the more orthodox and conservative older school owes its allegiance to a great scholar called Prabhakara and is known as the ‘Praabhaakara’ school, the later and not-so-orthodox school started by Kumarila Bhatta is known as the ‘Bhaatta school’. Both the schools have influenced the different schools of the Vedanta system of philosophy deeply.

Method of interpretation used in Meemamsa system of philosophy:

A particular Vedic passage which meaning or application is apparently ambiguous is taken up for discussion. Based on this, an ‘Adhikarana’ or locus of discussion is started. An Adhikarana contains six aspects viz. Vishaya (topic of discussion) Visaya (doubt) Purva-paksha (the apparent / incorrect view) Uttara Paksha (the correct, final view) Akshepa (objections on the view expressed above) Samadhana (reply to the objections raised). When an Adhikarana is started, first of all the Vedic passage or sentence being the topic of discussion is presented. Then the different possible meanings of the apparently ambiguous passage are mentioned. The incorrect view(s) is (are) first mentioned along with the basis (yukti) for substantiating them. Then the incorrect view is refuted by giving the logical reasons for this, and the correct and final view is presented along with the logical reasons. Further objections to this, if any, are raised, and the answers to those objections too are given and then the final concept obtained by the discussion is reiterated and declared. These are the aspects that constitute an ‘Adhikarana’.

In the Meemamsa system of philosophy authored by Sage Jaimini, there are an amazing one thousand Adhikaranas. Each of these Adhikaranas has given rise to concrete logical statutes that are known as ‘Nyayas’ and these too are one thousand in number. There is also a set of standard rules for interpreting the Vedic passages taken up for discussion. These are known as the “Taatparya-nirnaayaka-yuktis” or the logical reasoning that is useful in deciphering, analyzing and interpreting the exact meaning of the Vedic passages. They are as follows:

- Upakrama-Upasamhaarau – The introduction and conclusion

- Abhyasah – Reiteration

- Apurvata – Explanation given for the first time

- Phalam – Main intention of explanation

- Artha-vaadah – Commendations of the concept explained

- Upapattih – Reasons for accepting one particular interpretation while rejecting the other(s).

- Using the above parameters, the Vedic passages are interpreted in the right spirit, beneficial to everyone.

Vaisheshika – The Prameya Shastra

While the Nyaya Darshana deals extensively with the Pramanas or the means of knowledge, the Vaisheshika deals with the objects of knowledge that is obtained by means of the Pramanas. Vaisheshika attempts to identify and classify the entities that present themselves to human perception. It explains the nature of the world with seven categories: Dravya (substance), guna (quality), karma (action), samanya (universal), vishesha (particular), samavaya (inherence) and abhava (non-existence).

Vaisheshika contends that every effect is a fresh creation or a new beginning. Thus this system refutes the theory of pre-existence of the effect in the cause. Kanada does not discuss much on God. But the later commentators refer to God as the Supreme Soul, perfect and eternal. This system accepts that God (Ishvara) is the efficient cause of the world. The eternal atoms are the material cause of the world. Vaisheshika recognizes nine ultimate substances; five material and four non-material.

The five material substances are earth, water, fire, air and akasha. The four non-material substances are space, time, soul and mind. Earth, water, fire and air are atomic, but akasha is non-atomic and infinite. Space and time are infinite and eternal. The concept of soul is comparable to that of the self or atman. This system considers consciousness as an accidental property. In other words, when the soul associates itself to the body, only then it ‘acquires’ consciousness.

Thus, consciousness is not considered an essential quality of the soul. The mind (manas) is accepted as an atomic but indivisible and eternal substance. The mind helps to establish the contact of the self to the external world objects. The soul develops attachment to the body owing to ignorance, identifying itself with the body and mind. The soul is trapped in the bondage of karma as a consequence of actions resulted from countless desires and passions. It can be free from the bondage only if it becomes free from actions. Liberation follows the cessation of the actions.

This is but a brief introduction to the Tarka Shastra. This shastra (school of thought) is said to be invariably required for the study and proper understanding of any other system of thought and hence is rightly known as ‘Sarva-shastra-upakarakam’.

Tarka Shastra

The Tarka Shastra is one of the most important knowledge systems as it is mentioned in the Manu Smriti that all the Vedic texts as well as the teachings of the ancient seers are to be interpreted only in the light of correct and precise logic (Tarka) and thus properly understood. The Tarka Shastra consists of two principal streams of knowledge, viz. the Nyaya and the Vaisheshika. The Nyaya Darshana, which is also one of the six orthodox systems (darsana) of Indian philosophy, is important for its analysis of logic and epistemology.

The major contribution of the Nyaya system is its working out in profound detail the reasoning method of inference. Like the other systems, its ultimate concern is to bring an end to man's suffering, which results from ignorance of reality. Liberation is attained through right knowledge. Nyaya is thus concerned with the means of right knowledge. As mentioned earlier, in its metaphysics, Nyaya is allied to the Vaisheshika system, and the two schools were often combined from about the 14th century to form a unified ‘Tarka-Shastra’.

Its principal text is the Nyaya-sutras, ascribed to Gautama (c. 2nd century BC). On the other hand, the Vaisheshika, which was founded in the 2nd–3rd century AD by sage Kanada, is the complimentary school of thought which, when combined with Nyaya, forms the Nyaya-Vaisheshika school.

Nyaya Shastra – The Pramana Shastra

The four methods (Pramanas) of establishing true identity of a phenomenon or an object according to the Nyaya School are: Perception (Pratyaksha), Inference {Anumana), Comparison {Upamana} and Verbal Testimony (Aptavakya). Perception is the recognition and knowledge of the objects produced by their contact with various sense organs such as of sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell and the mind. Though it includes observation, it certainly embraces much more than that. Inference is the knowledge of the objects through the apprehension of some sign, which is invariably related to the inferred object. This is best illustrated by the following oft-quoted (though now outmoded) example "The hill is burning because it smokes and whatever smokes is burning." The order of events that take place when we infer this is: first the apprehension of the smoke in the hill, second the recollection of the universal relation between smoke and fire, and third the recognition of the fire in the hill.

An inference must also fulfill certain other essential requirements to be valid. Firstly, there should be a relation of agreement in presence (anvaya) between two things, i.e., in all cases where one is present, the other should also be present, e.g. wherever there is smoke there is fire. Secondly, there should also be uniform agreement in absence between them (vyatireka) e.g. wherever there is no smoke, there is no fire. Thirdly, no contradictory instance should be observed where one of them is present without the other (vyabhicaragraha).

Comparison is the knowledge of the object or phenomenon obtained by the establishment of a relation between a name and object so named or between a word and its denotation. This is illustrated by the following example: A man is told that an animal with a certain description is a cow. When he sees an animal for the first time, which particularly fits the description, he concludes by comparison that what he is seeing is a cow. The fourth method of establishing the identity of an object is by testimony (aptavakya), i.e. knowledge of the perceived and unperceived objects derived from the statement of authoritative sources, viz. scriptures such as the Vedas or the sayings of saints and sages.

This source of knowledge has been much criticized by Western scholars with the claim that utter acceptance of the authority of the Vedas has been a limiting factor and hindrance in the development of proper reasoning. It is important to note that for Indians their theories and philosophies were not of academic interest only. They actually lived those ideologies and also applied them in their practical sciences.

Recommended literature :

YOGA SUTRA of Patanjali, THE BHAGAVAD GITA, HATHA YOGA PRADIPIKA by Swami Swatmarama